To watch the YouTube video, click on arrow in thumbnail below:

On a summer’s day, in the lush, tropical country of Saint-Domingue, now known as Haiti, a slave woman named Ursule cradled her newborn son in her arms. She gazed out the window, her eyes taking in the green, fertile fields of the sprawling Bérard family sugar-cane plantation located on the banks of the Artibonite River, near the port town of Saint-Marc. This land was her home, where she lived and worked as a personal maid to Madame Berard. Even though she knew that her son, too, would be a slave, in her heart she dared to hope for greater things in his future. Little did she know that this baby boy was destined to play an important role, not only in the history of her people, but of the Catholic Church as well.

The infant had been given the name Pierre, after the owner’s father, Pierre Berard. The date of Pierre’s birth is recorded in many sources as June 27, 1766; however, based on the more recent research of journalist and biographer Arthur Jones, Pierre’s year of birth is now believed to have been 1781. His father’s name is unknown. The roots of Pierre’s family tree stretched back to Africa, where his great-grandmother Tonette had been born and raised before being taken across the Atlantic as a slave to toil on the sugar-rich soils of Saint-Domingue. Pierre’s grandmother, Zenobe Julien, had earned her freedom through years of loyal service to the Bérard family. Five years after Pierre’s birth, his sister Rosalie was born, who would become his steadfast companion throughout the years ahead.

As Pierre grew, the Bérard family, recognizing something special in the young boy, had him educated by their children’s tutors. In the grand house, far removed from the backbreaking labor of the fields, Pierre’s mind blossomed. Intelligent and eager, he learned to read, write, and think critically — skills that would one day prove instrumental in shaping not just his own destiny, but in helping and influencing many others. Jacques Berard allowed Pierre free access to his library, where the curious boy spent many hours avidly reading books on many diverse topics, further broadening his education. He was a playmate to the Berard children, and raised with knowledge of all the social niceties. Tall and mild-mannered, he was trained to courteously greet and serve the family’s guests, and had an excellent command of the French language, both written and spoken. He was also musically inclined and a talented fiddler. Pierre was baptized and raised a Catholic, and found solace in the rituals and teachings of the Church. Yet, as he matured, he couldn’t help but wonder at the contradictions between the Christian message of universal love and equality and the harsh realities of plantation life.

When the senior Bérards returned to France, their son Jean Bérard took over the plantation. Soon, tensions began to escalate, which eventually would lead to enslaved and free people of color uprising in the Haitian Revolution. In 1797, as conditions became more dangerous, Jean & Marie Berard fled for New York City, taking with them 16-year-old Pierre, his younger sister, Rosalie, his aunt, and two other house slaves. They arrived in the young country of the United States shortly after George Washington, its first President, had completed his two terms in office. They were among many French aristocrats, from St. Domingue and from Europe–where the French Revolution had ended in 1794–who were seeking refuge in America.

Once settled in a stylish rented house in lower Manhattan, Jean Bérard signed Pierre up as apprentice to a Mr. Merchant (first name unknown). He was a hairdresser, who taught Pierre the art of hair styling, a skill in which he quickly excelled. This was a wise move on Berard’s part, since the city was full of wealthy society women whose lifestyle required elaborate hairstyles for their frequent social engagements. Male hairdressers, while popular in France, were a fairly new phenomenon in America, where wealthy women generally had their hair done by their lady’s maid.

Berard allowed Pierre to keep most of what he earned as a hairdresser. Pierre quickly mastered all the latest hairstyles of the French, including powdered wigs and false hair additions, along with the chignons and face-framing curls that were trendy among the Americans. He became what one biographer described as “the Vidal Sassoon of his day.” His client list read like a “Who’s Who” of 18th-century New York society: Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton, wife of Alexander Hamilton, and their daughter, Eliza Holly Hamilton, were among his important clients, along with Catherine Church Cruger, known as “Kitty,” whose father would give the pistols to Hamilton for his duel with Aaron Burr. Another client, a prominent socialite named Mary Anna Sawyer Schuyler, also related to the Hamiltons, became Pierre’s close friend, referring to him as “my Saint Pierre.” Most of his women clients were Protestant, but they deeply admired Pierre’s devotion to his faith, along with his pious, kind and gentle nature. Hannah Farnham Sawyer Lee, Pierre’s first biographer and the sister of Mary Anna Schuyler, recounts, “He often quoted in his native language from the Sermon on the Mount, and the Beatitudes seemed to have found their way into his heart.”

Pierre also met some French emigrants in NY who knew the senior Berards in France, with whom he corresponded for decades, generously assisting his godmother, Aurora Berard, who had fallen on hard financial times in Paris. He also regularly corresponded with friends in Haiti. A prolific writer, his letters filled 15 bound volumes and served as part of the documentation submitted to the Vatican for his canonization process.

After a while, Jean Berard returned to Saint-Domingue to check on his property there. While in Haiti, he learned that his plantation was lost. He planned to return to New York; however, he developed pleurisy, an inflammation of the lungs, and died while still in Haiti. Soon after his death, his widow, Marie, learned that she was completely destitute. By then, Pierre was earning good money as a hairdresser. He voluntarily continued to care for the widow Marie, allowing her to lead a life of dignity, and assumed financial responsibility for the household. Marie eventually remarried to Gabriel Nicolas, who was also from Saint-Domingue. Pierre and Rosalie continued to live in the Nicolas household.

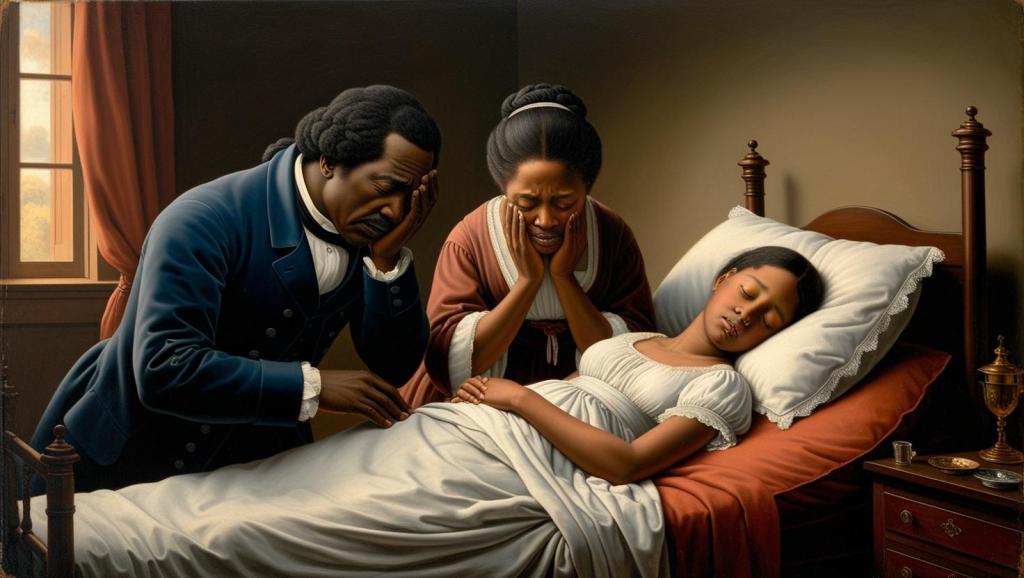

Eventually, Marie’s health began to fail. Pierre knew that having company lifted her spirits, so he encouraged her to entertain, and would buy tropical fruit and ice cream for the guests. Before they arrived, he would style Marie’s hair, adorning it with a flower as a finishing touch. In 1807, on her deathbed, Marie gave Pierre his freedom. In 1811, he bought the freedom of his sister, Rosalie, and also of his fiancé, Marie-Rose Juliette Gaston, whom he had known in Saint-Domingue.

Pierre’s relationship with the abolitionist movement was complicated. From the growing number of Haitian refugees in New York, he heard reports of murder and devastation from the island of his birth. Despite his intimate knowledge of slavery’s evils and his awareness of New York’s abolitionist movement, he refrained from active participation and hesitated to engage in America’s abolition debate, mindful of the immense toll paid to end slavery on his native island. He avoided anything that could incite violence, explaining, “They have not seen the blood flow as I have.” This stance led some Black Catholics in the 1990s to oppose his candidacy for sainthood, viewing him as too accepting of enslavement. However, the truth is that Pierre’s inner freedom transcended his legal status as a slave. He consciously chose to embrace God’s grace daily, becoming a powerful symbol of Divine generosity. Pierre himself articulated it this way: “I have never felt I am a slave to any man or woman, but I am a servant of almighty God who made us all. When one of His children is in need I am glad to be His slave.”

This perspective echoes that of Saint Josephine Bakhita, another former slave who expressed similar sentiments about her time of enslavement and her relationship with God. Pierre chose to exemplify human dignity and Christian charity to both the affluent and impoverished in the city. However, after gaining freedom, he chose the surname Toussaint, likely in honor of Toussaint Louverture [Loo-vah-TOUR], the leader of the Haitian Revolution. This choice suggests a connection to revolutionary ideals, despite his apparent reluctance to engage in overt abolitionist activities.

In his later years, Toussaint was reluctant to discuss the atrocities he had witnessed in Haiti. His approach focused on living out his faith through acts of kindness and generosity, becoming a beacon of hope and compassion in 19th-century New York.

Pierre and Juliette wed on Aug. 5, 1811. For the next four years, they continued to board at the Nicolas house. In 1815, Gabriel Nicolas, who had remarried, moved down South with his wife, and the Touissants purchased a home of their own in Manhattan. Although they never had biological children, when Pierre’s sister Rosalie died of tuberculosis, he and Juliette adopted Rosalie’s daughter, Euphemia. They enrolled Euphemia in a school for Black children in New York. Pierre tutored her in French and taught her to write in both French and English. She also had piano lessons from an accomplished musician named Cesarine Meetz, who gave recitals at City Hotel. Cesarine’s father, Raymond, owned a musical depository on Maiden Lane and was a minor composer and music teacher. When Euphemia died at the age of 14, also of tuberculosis like her mother, Pierre and Juliette were devastated with grief, for they had loved her as their own child.

The Touissants lived a life of charity, compassion and generosity in New York City. They frequently visited the Orphan Asylum, bringing joy to the children with baked treats as well as financial support. Their home became a sanctuary, where they fostered a succession of orphan boys, providing them with education and vocational training. Pierre and Juliet established a credit bureau and an employment agency, offering crucial support to those in need. Their home also served as a refuge for priests and travelers seeking shelter. Pierre’s bilingual skills in French and English made him an invaluable asset to Haitian refugees arriving in New York. He assisted these newcomers by organizing sales of goods, helping them secure funds for their livelihood.

Pierre and his family attended St. Peter’s Church on Barclay Street. He went to Mass every morning at 6:00 a.m., until in his later years illness prevented him from doing so. He was devoted to the rosary and had an excellent command of Scripture. St. Peter’s was the same parish that Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton had attended for a few years after her conversion to Catholicism in 1805, before moving to Maryland, where she founded the Sisters of Charity, America’s first community of nuns. There is no record of Seton and Touissant ever meeting one another; however, he played an important role in later raising funds for the Sisters of Charity’s orphanage in New York, even though it admitted only white children.

The Touissants’ contributions to the Catholic community were significant, including fundraising for the construction of Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Mulberry Street. They supported various Catholic institutions, including orphanages and schools, and also helped establish the first Catholic school for Black children in New York City, at St. Vincent de Paul on Canal Street. Pierre Touissant is called the “father of Catholic Charities,” because his legacy of compassion and service laid the foundation for what would later become the Catholic Charities organization.

During a cholera epidemic, Pierre fearlessly crossed barricades to care for quarantined patients. On at least one occasion, he brought a sick priest back to his house to nurse him back to health. He also showed heroic charity in his response to the outbreaks of yellow fever that occurred every summer in New York, something he had seen often back in Saint-Domingue. Hannah Sawyer Lee wrote the following about one such epidemic:“When the yellow fever prevailed in New York, by degrees Maiden Lane was almost wholly deserted, and almost every house in it closed. One poor woman, prostrated by the terrible disorder, remained there with little or no attendance, till Toussaint, day by day, came through the lonely street, crossed the barricades, entered the deserted house where she lay, and performed the nameless offices of a nurse, fearlessly exposing himself to the contagion.”

Despite his success, Toussaint faced significant challenges as a free Black man in New York, where slavery remained legal until 1829. He risked abduction by bounty hunters, and was barred from public transportation, forcing him to walk to his clients’ homes. His Catholicism added to his vulnerability, as anti-Catholic prejudice was widespread in New York at the time. Conversely, his reputation as an entrepreneur and highly-skilled master of his trade made him welcome in the homes of New York’s society families, not only as a hairdresser but as a trusted friend and confidante. Many clients came to view Pierre as more than just a hairdresser, seeking his advice on personal matters. His wisdom and discretion made him a trusted advisor. His clients were deeply impressed by his staunch commitment to discretion and his refusal to engage in gossip. This level of trust allowed them to confide in him freely, knowing their secrets were safe. One client remarked, “It was like the confessional to talk to Toussaint, you were so sure of his secrecy.” This steadfast refusal to share gossip was seen as evidence of his strong moral character. When pressed for information, Pierre would simply state, “Toussaint, Madame, is a hairdresser. He does not gather news.” This polite but firm response became well-known among his clientele, further establishing his reputation for discretion.

A significant friendship blossomed on Franklin Street in New York City, where Pierre and Juliette lived at number 144. Just down the street at number 70 resided the Moore siblings – Nathaniel Fish Moore, an enthusiastic amateur photographer and the future president of Columbia University, and his sister Sarah Ann. Toussaint’s skillful hands had long been tending to Sarah Ann’s hair, their relationship evolving from that of stylist and client to genuine friendship. Evidence of their bond survives in the Pierre Toussaint papers at the New York Public Library, where two letters from Sarah Ann reside. One, undated, simply requests a hairdressing appointment. The other, penned in 1840, speaks of a more personal connection – Sarah Ann had thoughtfully brought Pierre a rosary from her and Nathaniel’s pilgrimage to the Holy Land.

It was through this connection that Toussaint came to sit for Nathaniel Fish Moore’s camera. Nathaniel, ever eager to practice his craft, captured a striking portrait of Toussaint in his later years. For decades, this photographic image lay dormant, passed down through the Moore family until 1944, when William Hodges, Sarah Ann’s grandson, donated it along with other salt prints to Columbia University’s Columbiana Collection. Initially misidentified and incorrectly credited, the photograph’s true significance remained hidden until many years after Pierre’s passing. But more about that later!

Through the 1820s and early 1830s, Pierre Toussaint’s fortune grew steadily through his tireless work.His days often stretched beyond 12 hours as he traversed New York’s streets, styling hair in the city’s most prestigious homes. Yet, this demanding work was not for personal gain; rather, it was a means to generate more resources for the less fortunate. When a friend suggested he had amassed enough to retire comfortably, Toussaint responded with characteristic selflessness: “Madam, I have enough for myself, but if I stop work, I have not enough for others.”

In 1835, disaster struck New York City, when the Great Fire of New York engulfed lower Manhattan, destroying between 530 and 700 buildings across 13 acres. Witnesses described the inferno as “immense iron furnaces in full blast,” with copper roofs melting and “fiery tongues of flame” leaping from buildings. This catastrophe is believed to have cost Pierre investments equivalent to almost a million dollars in today’s currency. Despite this significant financial setback, he persevered in his charitable endeavors.

Hannah Sawyer Lee eloquently captured the essence of his philanthropy in her 1854 memoir: “It must not be supposed that Toussaint’s charity consisted merely in bestowing money; he felt the moral greatness of doing good, of giving counsel to the weak and courage to the timid, of reclaiming the vicious, and above all, of comforting the sick and sorrowful.”

The 1840s brought stark reminders of the persistent racism in American society. Although New York had abolished slavery, prejudice and violence against Black individuals remained commonplace. In 1842, Toussaint and his wife faced a painful incident at Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Mulberry Street – a church whose construction he had helped finance. Unaware of his prominent status, ushers turned them away due to their race. As they turned to leave, some Cathedral trustees saw what was happening and rushed to apologize and welcome them into the church. But the damage had been done, underscoring the pervasive discrimination of the era. By contrast, Pierre’s own charity and inclusivity stood as a shining example of true Christian virtue, to be emulated not only in his day, but in ours.

Though he continued to grow steadily in spiritual strength and beauty, Pierre gradually began to decline physically during the following decade. On May 14, 1851, his beloved wife and partner, Juliette, died and was buried in the cemetery of St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral beside their adoptive daughter, Euphémia. It was at this time that Pierre demonstrated the assertiveness he could summon when it truly mattered. At Juliette’s funeral, he requested that only Black attendees follow the procession to the graveyard, although white mourners were welcome at the graveside. This practice was repeated at his own funeral.

After Juliette’s death, Pierre’s health further deteriorated. He became increasingly inactive and was often bedridden. Two days before he died, he uttered the words, “God is with me.” When someone asked him if he wanted anything, he replied, “Nothing on Earth.” Those were his last recorded words. Pierre Toussaint entered into his eternal home on June 30, 1853.

At his funeral Mass, St. Peter’s Church overflowed with mourners of all types – rich and poor, Black and white – wishing to pay their respects to the man whose kindness, dignity and charity illuminated the lives of everyone he encountered. Pierre Toussaint had managed the incredible feat of displaying true Christian charity, compassion, respect and mercy that transcended all the levels of society in which he moved. Father Quinn, who gave the eulogy, said that Pierre Touissant was “one who always had wise counsel for the rich and words of encouragement for the poor.”

As the funeral service concluded, Pierre’s white friends and associates honored his final request, stepping back to allow members of the Black community to bear his casket through the streets to St. Patrick’s Cemetery on Mulberry Street, as they had for Juliette two years earlier. At the graveside, people from all walks of life united in prayer as Toussaint was laid to rest beside his wife Juliette and adopted daughter, Euphemia.

New York’s newspapers paid tribute to Pierre Toussaint’s passing with lavish praise. One obituary eloquently stated: “His charity was of the efficient character which did not content itself with a present relief of pecuniary aid, but which required time and thought by day and by night, and long watchfulness and kind attention at the bedside of the sick and the departing.”

In 1854, Hannah Sawyer Lee’s biography, “Memoir of Pierre Toussaint, Born a Slave in St. Domingo,” published in Boston, became crucial in preserving details of his extraordinary life through notes left by her sister, Mary Anna Schuyler, and other sources. But in the turbulent decades following Toussaint’s death, as America grappled with political upheaval leading to the Civil War and its aftermath, his remarkable story faded from public memory, persisting mainly as oral history within Haitian-American and Black Catholic communities. A few decades later, the Touissant archives at the NY Public Library were compiled by Mary Ann Schuyler’s granddaughter Georgina.

But these did not draw much public attention until the 1930s, when Garland White, Jr., a young African-American student preparing for Confirmation challenged his teacher, a seminarian named Charles McTague, with the words, “You can’t name me one Black Catholic that white people respected!” McTague did not back down from the challenge. He managed to locate a Jesuit priest named John LaFarge, who remembered his grandmother’s stories about a devout Black man who had been her hairdresser for many years. McTague rediscovered Toussaint’s family gravestone in the Mulberry Street cemetery, where the inscription had faded to the point of being illegible. This discovery generated new interest in Toussaint’s extraordinary life and works.

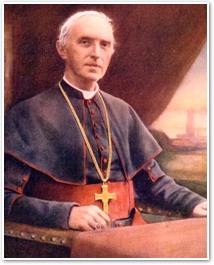

In the 1950s, research and promotion of Pierre Touissant’s life was begun by the John Boyle O’Reilly Committee for Interracial Justice, an Irish-American group dedicated to social justice and equality. In 1951, a petition for the canonization of Pierre Toussaint was begun, and Cardinal Francis Spellman blessed a plaque to mark Touissant’s headstone. Spellman’s successor, Cardinal Terence Cooke, initiated the cause of canonization in 1968, which gained momentum over the following decades.

Fast forward to 1990, when, as part of Toussaint’s canonization process, his remains needed to be exhumed, examined and identified. Columbiana Curator Hollee Haswell provided the photograph taken in 1850 by Nathaniel Fish Moore to a team of forensic anthropologists, who compared it against Toussaint’s exhumed skull, leading to positive identification. Cardinal John O’Connor arranged for Pierre’s remains to be interred in the crypt beneath the altar of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, an honor usually reserved only for high-ranking clerics. Pierre Touissant thus became the only lay person, and the only Black person, to be buried in this crypt. A portrait of Touissant by Hunt Slonem now also hangs in the Cathedral.

In 1996, Pope John Paul II declared Pierre Toussaint “Venerable,” advancing him one step closer to sainthood. As of now, Toussaint’s canonization cause awaits an intercessory miracle — specifically, the instantaneous, complete, permanent, and medically-inexplicable healing of a serious medical condition — to progress to the next step of beatification. A second miracle is required for canonization. He is one of six North Americans under consideration for sainthood, potentially becoming the first Black North American saint.

Pierre’s legacy continues to thrive in the Archdiocese of New York and beyond. The Pierre Toussaint Guild, actively involved in advancing his cause for sainthood, also works to share his inspiring story globally. The Pierre Toussaint Scholarship Fund, managed by the archdiocese’s Black Ministry Office, perpetuates his mission by providing financial grants, mentorship, and opportunities for students to develop both their faith and careers. The foundation’s impact extends internationally, supporting the College Pierre Toussaint in Sassier, Haiti, enabling young Haitians to acquire skills to serve their community. In Miami, Florida, the Pierre Toussaint Haitian-Catholic Center bears his name, offering support services to Haitian immigrants. Though there are too many to list here, Pierre Touissant’s legacy extends to charitable and education institutions throughout the United States and beyond.

Additionally, Toussaint’s memory is honored through various public recognitions. A series of portraits in Gracie Mansion commemorates his good works. In April 2021, a significant portion of Church Avenue in Brooklyn, New York, was co-named Pierre Toussaint Boulevard. Additionally, the intersection near St. Peter’s Church in Manhattan, Toussaint’s former parish, was named after him in 1998. Most recently, in February 2024, Toussaint was featured in the New York Times’ “Overlooked No More” series of articles, which highlight remarkable individuals whose deaths originally went unreported in The Times.

In 1999, at a Mass in Toussaint’s honor, Cardinal O’Connor said, “If ever a man was truly free, it was Pierre Toussaint…. If ever a man was a saint, in my judgment, it was Pierre Toussaint. … No one can read this man’s life…without being awed by his holiness. He is now buried beneath this high altar with all of the bishops, archbishops and cardinals of New York. It will be a great privilege for me to be buried in a vault in the same section with Pierre Toussaint.” Cardinal O’Connor further stated that it was not necessary to wait for Pierre’s official sainthood to emulate his virtues. “Beatified or not,” he said, “Pierre Toussaint remains a wonderful model, and I wish he were here.”