To watch the YouTube video, click on the arrow in the thumbnail below:

I learned about St. Lucy at a very young age, when my mother told me she believed that her prayers to this great saint saved my eyesight when I was an infant. It was customary at that time to put silver nitrate into the eyes of newborn babies to prevent bacterial infections that can occur during birth. Unfortunately, in my case too much silver nitrate was applied to my eyes, which can cause severe inflammation, corneal melting and scarring, and significant vision impairment. My mother said that for a while my eyes were stuck shut, and the doctors didn’t know if I would suffer vision loss. Being Italian-American and knowing that Santa Lucia, greatly venerated in Italy, is the patron saint of eyes, my Mom fervently prayed to her on my behalf. Fortunately, my eyes cleared up, and I suffered no permanent damage to my vision. (In the 1980’s, erythromycin replaced silver nitrate as a precautionary treatment for newborn babies’ eyes.)

As a result of this incident, St. Lucy always has held a special place in my heart, and I’ve had a devotion to her all my life. I even picked Lucy as my confirmation name. I have invoked her intercession whenever I or a loved one have had any type of eye problem, and she has always helped us.

Because Lucia lived so long ago, most of her history has been lost to time. We do have some basic facts about her, as well as legends that have persisted over the centuries. The following account is the one that has stood the test of time and seems the most plausible:

Lucia was born in Siracusa (Syracuse) in Sicily, Italy in or around the year 283. Her parents were wealthy members of the nobility. Her father was of Roman origin, but there seems to be no record of his name. He died when Lucia was five years old. Her mother’s name was Eutychia and she was seemingly of Greek ancestry. Lucia converted to Christianity at a young age and developed a devotion to St. Agatha, a virgin who was martyred in Catania, Sicily, around 251 AD. Like Agatha, Lucia consecrated her virginity to God and vowed never to marry.

Her mother, Eutychia, is said to have suffered from a chronic hemorrhagic condition and feared that she did not have long to live. She worried about Lucia being left alone after her death, so she arranged Lucia’s betrothal to a wealthy young man from a noble pagan family. It’s possible that Eutychia was unaware of Lucia’s vow of virginity, or else her concern for Lucia’s future caused her to ignore the vow. But somehow, Lucia managed to delay the marriage for the next several years.

Having heard of the many cures reported by people who had traveled to St. Agatha’s tomb in Catania to invoke her intercession, Lucia persuaded her mother make a pilgrimage with her to the tomb to request St. Agatha’s intercession to cure Eutychia of her malady. Lucia hoped not only for the healing of her mother, but that the healing might convince her mother that Lucia’s Christian faith was indeed the best choice for her life.

Lucia and Eutychia traveled to Catania, which was less than 50 miles from their home, and prayed at St. Agatha’s tomb for Eutychia’s healing. While there, Lucia had a dream in which St. Agatha told her that Eutychia would be cured because of Lucia’s faith. Agatha also told her, “Soon you will be the glory of Siracusa, as I am of Catania.” Upon awakening, Lucia cried to Eutychia, “O mother, mother, you are healed!”

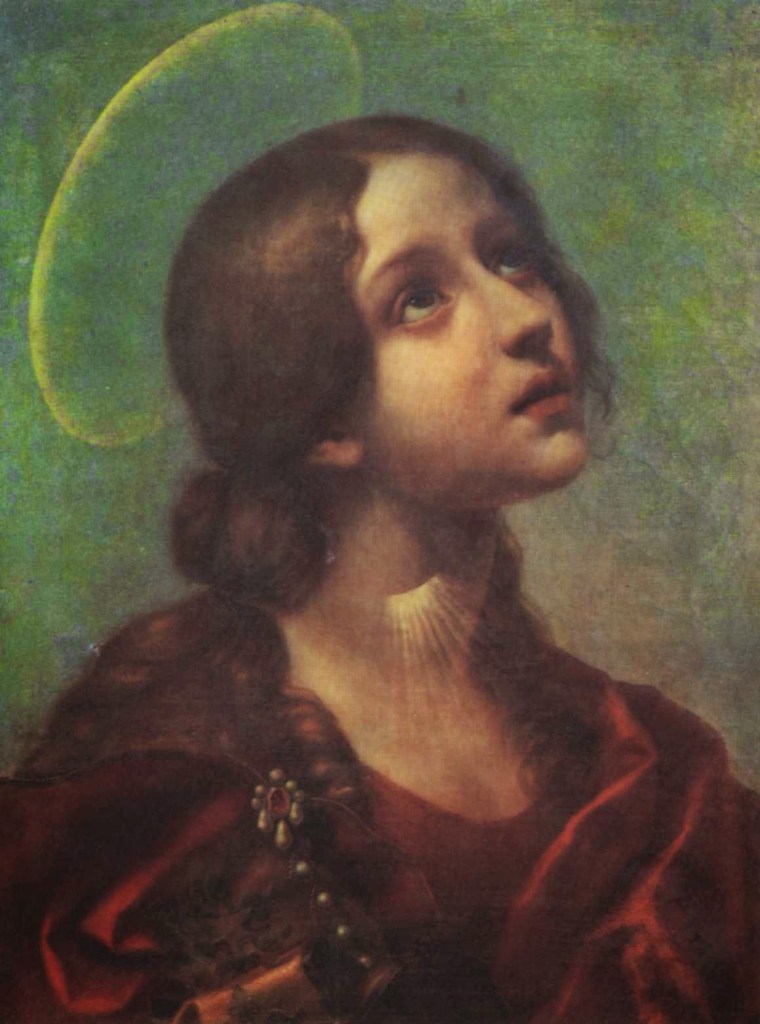

14th-century painting by Giovanni di Bartolommeo Cristiani

Eutychia’s condition did indeed improve, so when they returned home Lucia took the opportunity to convince her mother to allow Lucia to distribute her dowry money to the poor and live the celibate life she had vowed to God years earlier. At first, Eutychia tried to persuade Lucia that it would be imprudent to dispose of all her money straightaway, and suggested that Lucia instead bequeath it in her will. Lucia is reported to have replied, “Whatever you give away at death for the Lord’s sake you give because you cannot take it with you. Give now to the true Savior, while you are healthy, whatever you intended to give away at your death.” Eutychia finally agreed, and Lucia began to distribute her dowry money to the poor.

In 303 A.D., the Roman Emperor Diocletian issued an edict that outlawed the Christian religion throughout the Roman Empire. Christians were forbidden to gather for worship, their churches were destroyed, and sacred Christian texts were abolished. Christian civil servants or members of the nobility were stripped of their ranks, and their belongings confiscated. Christians were forced to offer sacrifice to the Emperor and the Roman gods. To refuse meant torture and even execution.

Tradition says that Lucia visited the poor, the homebound, and Christians hiding in the catacombs, delivering wheat and bread to them. Because she often went at night to avoid being discovered, she carried a lamp to light her way. Sometimes, to keep her hands free to carry the provisions, she wore on her head a wreath crowned with candles. An early Christian text records her as telling her fellow Christians by way of encouragement: “To God’s servants the right words will not be wanting, for the Holy Spirit speaks in us. All who live piously and chastely are temples of the Holy Spirit.”

Eventually, gossip about Lucia’s donation of her dowry to the poor reached her prospective bridegroom. He became enraged, either because of the rejection of realizing that Lucia had no intention of becoming his bride, or because of his greed over the loss of her dowry money – and probably both. He reported to Paschasius, the Governor of Siracusa, that Lucia was a practicing Christian.

Lucia was arrested and questioned by the Governor. He ordered her to offer a sacrifice to the Roman gods, but of course she refused.A later text on Roman martyrs reports her to have said: “I know but one sacrifice pure and full of honor, which I can offer. This is to visit orphans and widows in their tribulation, and to keep oneself unspotted from the world. For three years, I have daily offered this sacrifice to my God and Father, and now I long for the happiness of offering myself to Him as a living victim. His holy will be done.”

Lucia also told the Governor that his worship of the Roman Gods would condemn his soul before the one true God, and that the reign of Diocletian would soon come to an end. This so outraged Paschasius that he ordered her to be taken to a brothel and forced into prostitution, the ultimate mockery of her Christianity and vow of virginity. Legend tells, however, that Lucia was so filled with the Holy Spirit that she became immovable. No efforts on the part of her captors was able to budge her, not even when they attempted to drag her by tying her to the yoke of a team of oxen. They then surrounded her with wood and set it on fire, but the flames did not harm her.

To further torture her, Lucia’s eyes, which were reportedly very beautiful, were gouged out by her captors. Another account says that Lucia gouged them out herself, in an effort to make herself unattractive to her suitor or any man who would attempt to defile her. (Personally, I find the torture theory to be more plausible than the self-mutilation theory.) Her frustrated captors finally succeeded in killing her by piercing her through the neck with a sword. Early literature on the martyrs reports Lucia to have said as she was dying: “O Siracusa, O place of my birth, as Catania finds its safety and glory beneath the guardianship of my sister Agatha, so shall you be shielded by me, if you are willing to embrace that Faith for the truth of which I shed my blood.”

Whatever the real cause of Lucia’s loss of her eyes, when her body was being prepared for burial, it was discovered that her beautiful eyes had been restored by God. This is the reason Lucia is honored as the patron saint of those suffering from blindness and eye diseases, and why she is most often depicted in art holding her eyes on a golden platter.

Whatever one believes about the legends that have sprung up around Lucia’s life, one thing is clear: She had to have been a woman of a particularly heroic nature, because devotion to her grew exponentially after her death. The first writings about her were in the Acts of the Martyrs, written in the late fifth century. Many miracles were attributed to her, and by the sixth century she was included in the Sacramentary of Pope Gregory I, and also in the Roman Martyrology. She was honored throughout the Christian world until the Protestant Reformation. In England, her feast day of Dec. 13 was at one time considered a holy day, on which no work except farming was allowed. Today, St. Lucy is still venerated in the Roman Catholic, Orthodox, Lutheran and Anglican Churches.

Lucy holds the honor of being one of several women saints mentioned in the Roman Catholic Eucharistic Prayer I said at Mass: “To us, also, your servants, who, though sinners, hope in your abundant mercies, graciously grant some share and fellowship with your holy Apostles and Martyrs: with John the Baptist, Stephen, Matthias, Barnabas, Ignatius, Alexander, Marcellinus, Peter, Felicity, Perpetua, Agatha, Lucy, Agnes, Cecilia, Anastasia, and all your Saints….”

St. Lucy is the patroness of Siracusa and Perugia in Italy, the town of Olon in Ecuador, and Guane, Santander, Colombia. The island of St. Lucia in the Caribbean is named after her. She is the patron of authors, glaziers, laborers, martyrs, peasants, saddlers, salesmen, and stained glass workers. Besides her special patronage of people with blindness and diseases of the eye, she is invoked against hemorrhages, dysentery, and throat infections. In art, she is usually pictured carrying her eyes on a golden plate, and sometimes holding a palm branch, symbolic of martyrs. She also is sometimes depicted with the symbols of a lamp, dagger, sword, or two oxen.

St. Lucy’s current feast day is December 13, during Advent. Before the calendar reforms, her feast day was also the Winter Solstice. Since this was the shortest and darkest day of the year, and because her name, Lucia, derives from the Latin word for light (“lux”), she stands as a symbolic bearer of light in the darkness. Thus, her feast day became a festival of light.

One legend tells that during a famine in Italy, ships filled with wheat sailed into the harbors on St. Lucy’s feast day, saving the people from starvation. Because of this, in Sicily it is traditional to make “cuccia,” a dish of boiled wheat berries, mixed with ricotta and honey or served as a soup with beans, to celebrate her feast day. Croatians plant wheat in a pot indoors on Dec. 13, and by Christmas, when the shoots have emerged, they are put next to the Nativity manger as a gift to the Christ Child and a symbol of the Eucharist, which is made of wheat.

A similar legend states that on the Winter Solstice during a famine in Sweden, a boat came into sight sailing across the lake. St. Lucy could be seen at the prow of the boat, dressed in white with a heavenly light emanating from her. Upon the boat’s docking at the shore, she handed out sacks of wheat to the starving people. To commemorate this, Scandinavians bake a sweet saffron bread called “Lussekatter,” and bring it to the poor, sick, and shut-ins on Dec. 13. In Scandinavian countries, on “lucienatt” (Lucy night), there is a procession of schoolchildren carrying candles and singing the “Santa Lucia” song. They are led by a girl dressed as Lucia in a white dress, with the wreath crown of candles on her head. The “Santa Lucia” song, which is popular in many countries, was written by the Neapolitan composer Teodoro Cottrau in 1850. There is a Scandinavian version as well, using the same melody but with Swedish lyrics. In some villages in the Philippines, a St. Lucy novena (9 days of prayer) is held before her feast day. There is a procession of St. Lucy’s image every morning at the village center during the 9 days of the novena.

Even though Lucy lived so long ago that there is little known about her, it is extraordinary that she has remained a beloved and venerated figure for over 1700 years. This fact stands as an enduring testimony to her sanctity, her courage, and her great love of Christ and her fellow humans. Her light still shines brightly today, as it did so many centuries ago. It is a light that is sorely needed in our present time, which is so often enveloped in the darkness of hatred, violence and evil. St. Lucy stands near to us as a steadfast friend in the communion of saints, ready to intercede with God on our behalf. For myself, I am grateful for her intercession in saving me from blindness, allowing me to be able to see the light and beauty of God’s creation. Grazie, Santa Lucia!

Traditional Prayer to St. Lucy:

“Saint Lucy, you did not hide your light under a basket, but let it shine for the whole world, for all the centuries to see. We may not suffer torture in our lives the way you did, but we are still called to let the light of our Christianity illumine our daily lives. Please help us to have the courage to bring our Christianity into our work, our recreation, our relationships, our conversation – every corner of our day.

By your intercession with God, obtain for us perfect vision for our bodily eyes and the grace to use them for God’s greater honor and glory and the salvation of all people. Saint Lucy, virgin and martyr, hear our prayers and obtain our petitions. Amen.”