To watch the YouTube Video, click arrow on thumbnail below:

On a warm, late April day in 1586, a servant woman in Lima, Peru experienced a miraculous vision while gazing upon the newest member of the noble Flores family. Before her very eyes the infant girl’s face seemed to transform into a beautiful rose in full bloom. The astonished servant rushed to share her vision with the child’s mother, who agreed it was a Divine sign. From that day forward, the baby, who had been baptized Isabel Flores de Oliva on April 20, was called “Rose.”

Rose’s father was Gaspar Flores, a Spanish Imperial Cavalry member, whose family had originated in Spain and later emigrated to Puerto Rico. Her mother, 26-year-old María de Oliva y Herrera, was a criolla, which meant she was a female of European, typically Spanish, ancestry who was born in Spanish America. She also had Inca blood. Rose was their seventh child.

The era of Rose’s birth was marked by stark contrasts. Fifty years after Francisco Pizarro’s conquest of Peru for Spain, Peru’s vast mineral wealth enriched Spain but left the indigenous people impoverished and oppressed. This period also saw the Catholic Church’s reform following the Council of Trent. The religious climate in Peru was complex, with Christianity thinly overlaying native beliefs and superstitions. The forced conversion of indigenous Peruvians to Christianity without proper instruction led to widespread reversion to pagan beliefs within fifty years of Spanish arrival in Peru. The Spaniards’ harsh response only intensified the Peruvian resistance, creating a seemingly hopeless situation for both parties. As little Rose grew, she would become keenly aware of her historical context, and would pray fervently for her homeland.

Rose was a child of extraordinary beauty, her pink cheeks indeed reminiscent of a blooming rose. Her heart was devoted to God from a tender age. At just three years old, Rose demonstrated remarkable fortitude when she endured a severe finger injury in silence, not informing her parents. When discovered, the injury required the removal of her fingernail, a procedure she bore without a whimper or tear.

Rose loved flowers and often used them in her spiritual practices. When she was five years old, she constructed a little chapel in the family garden, where she spent countless hours in prayer. At the time of her first Confession, it is said that, strangely enough, she got permission from her confessor to make a vow of virginity. Since, due to her young age, this would not have been any kind of binding vow, and it was unlikely that she even truly understood its meaning yet, the priest’s permission probably was just a way of pacifying her wishes and encouraging her piety.

When she was confirmed in 1597, she officially chose “Rose” as her Confirmation name. Her mother, Maria, proud of Rose’s beauty, adorned her with wreath crowns of the garden’s finest roses. Initially resisting elegant attire, Rose ingeniously concealed thorns beneath the rose crown, transforming it into her personal “crown of thorns.” When she made her First Communion, Jesus promised her that if she fasted for His sake, He would sustain her. From that time on, for the rest of her life she gave up eating meat.

Rose had a deep devotion to the Infant Jesus and His Blessed Mother and spent countless hours praying before the Blessed Sacrament. She received Communion three times a week. Although she would have liked to receive daily, in those days young girls were forbidden to go out unless accompanied by an adult woman, and Maria was not always available, perhaps deliberately. Later in her life, Rose was able to receive Communion daily, which was an extremely rare practice at that time.

After reading a book about St. Catherine of Siena, the impressionable young girl adopted the saint as her personal role model. Emulating St. Catherine, Rose fasted three times a week, donned coarse clothing, and cut her beautiful hair short. She concealed her cropped locks with a veil to avoid her parents’ disapproval. When Maria eventually discovered it, she was very angry.

In Rose’s teenage years, her family faced financial hardship when her father’s gold-mining venture failed, leaving them impoverished, with seven children still living at home. Rose, ever resourceful, stepped up to support her family by selling flowers from her own garden and creating exquisite lace and embroidery. Her needlework was of the highest quality, with remarkable beauty and delicacy. Despite long hours of labor, Rose dedicated her evenings to prayer and acts of penance.

Maria had grand aspirations for her beautiful daughter, hoping to secure a marriage into one of Peru’s wealthy and prominent families. She orchestrated opportunities for potential mothers-in-law to admire Rose, but these efforts were in vain, because, contrary to her mother’s wishes, Rose felt a Divine calling to a life of virginity.

When Rose realized she was attracting the notice of suitors, she attempted to deflect their attention by rubbing crushed hot peppers on her beautiful face and lime juice on her hands to roughen them.

SO WHAT DID ROSE REALLY LOOK LIKE?

We sometimes hear about saints, like Rose of Lima, who were said to be beautiful. But in most cases, we don’t have any idea what they really looked like. However, in a groundbreaking scientific endeavor, the face of Saint Rose of Lima has been reconstructed using advanced technology. A team of scientists from the University of Saint Martin de Porres in Peru collaborated with the Brazilian Anthropological and Dental Legal Forensics Team to analyze and reconstruct the saint’s facial features. Here I am showing two views of her reconstructed face.

The project involved not only Saint Rose but also two other saints. At the clinic, researchers employed CT scans to create detailed images of the skulls. This non-invasive technique, commonly used in medical diagnostics, allowed for precise 3D digital modeling of the saints’ cranial structures.

Saint Rose of Lima’s reconstructed face was the first to be unveiled. According to researchers, the reconstruction revealed “a pretty woman with soft features and a well-distributed face.” Notably, her eyes appear larger than in classical portrayals.

At age 17, with the help of her brother, Rose constructed a small hut in the family garden. This humble abode became her sanctuary where, with the permission of her confessor, she retreated to devote herself fully to work, prayer, and penance. She offered her life in reparation for the sin and corruption in her society.

Rose worked hard to support her household and was obedient to her parents, except in their insistence that she marry. This sticking point caused a decade-long conflict with her parents, during which Rose exercised great patience and prayed for guidance. She eventually discerned that it was not God’s will for her to enter a convent, and she received a sign that she, like her idol St. Catherine of Siena, was to become a Dominican Tertiary and continue to live at home.

At age 20, she finally received her parents’ permission to join the Third Order of St. Dominic, donning the habit and taking a vow of perpetual virginity. Instead of entering a convent, she stayed in the hut in her parents’ garden, intensifying her prayer and penances.

Despite her life as a partial recluse, Rose remained acutely aware of the oppression in Peruvian society. She became renowned in Lima for her virtue and acts of charity, caring for the sick and hungry in her community, often bringing them to her hut to care for them. Her garden soon became the spiritual nucleus of Lima. She learned how to make herbal medicines, which she distributed to the poor, and occasionally visited hospitals to nurse the sick.

Rose was blessed with miraculous abilities. Seeking Divine intervention from the Child Jesus to cure the sick, her prayers often were answered with remarkable healings. At times, she also worked wonders to provide sustenance for her family. One such example was when her father, Gaspar, had overextended himself financially outfitting two of his sons who had been granted the prestigious honor of joining a royal galleon to battle the British. In addition, the family had also recently celebrated the wedding of another daughter, further straining their already precarious finances. The normal income from Rose’s needlework was not coming in, because she was working on a trousseau for her sister. The situation reached a critical point when Gaspar received an ultimatum from his creditors: produce the money by ten o’clock the following morning or face dire consequences, including the possibility of imprisonment. Gaspar, his voice heavy with resignation uttered the despairing words, “All is lost! It is the end!”

Determined to help, Rose accompanied her equally dejected brother to church, continually encouraging him to keep faith. In church, Rose prayed harder than she ever had before. As they exited the church, a stranger approached Rose, pressing a packet of money into her hands, saying, “I have this package of money for the señorita. Give this to your father for his present needs.” To the family’s astonishment and relief, the sum was exactly the same as Gaspar’s debt.

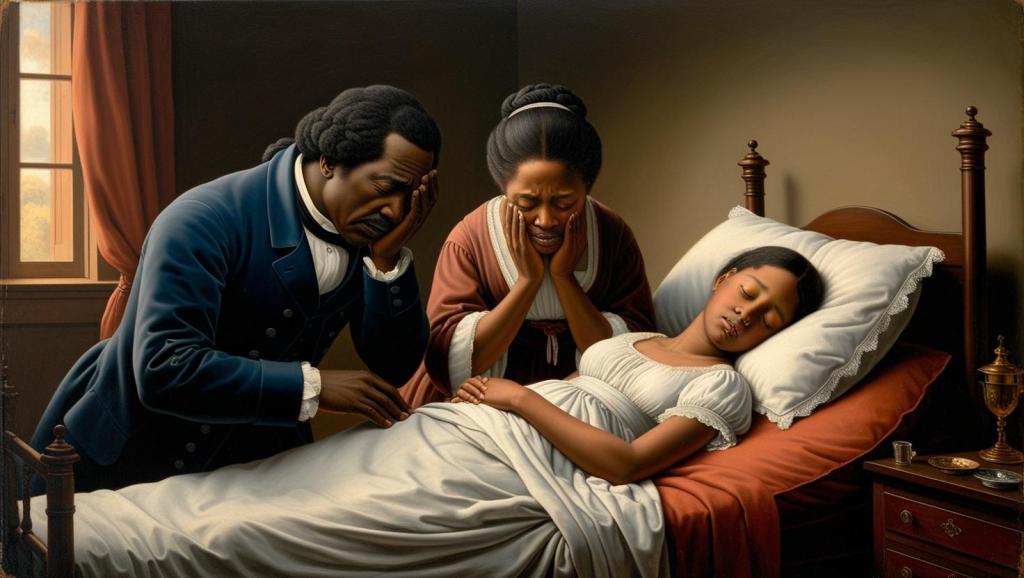

Rose’s boundless charity and selfless devotion to the needy earned her the affectionate titles “Mother of the Poor” and “The Rose of Lima.” Her commitment to the sick was particularly noteworthy. She personally dressed the wounds of those suffering from cancers, ulcers, and repulsive sores. Her compassion knew no boundaries. Although many of these women were beyond medical help, Rose provided comfort and solace in their final days. She dedicated herself to caring for the most neglected and abandoned women in Lima, regardless of their race or social status. She would seek out these women, bring them home with her, and tend to their needs with tireless dedication. She devoted considerable time to caring for the indigenous women of Peru, who were often the most forsaken in society. Her compassion and love for God deeply impressed those who met her, and her works of mercy laid the foundation for social work in Peru.

Maria found her daughter’s work distasteful, but Rose, guided by Divine inspiration, found ways to overcome her mother’s objections. However, the intensity of her charitable work took a toll on Rose’s health and appearance. Her once rosy cheeks and fair complexion faded, leaving her looking pale and gaunt. One day, while walking to church with her mother, Rose overheard someone commenting that her altered appearance was a sign of sanctity. Troubled by possible temptation towards spiritual pride, Rose fervently prayed to God to restore her healthy appearance. She wished to keep her work and fasting hidden from others, and God granted her request.

One day, a miraculous event unfolded that would forever be associated with Saint Rose. Dutch pirates, emboldened by their victory over the Peruvian fleet, set their sights on the city with sinister intent. Driven by the fervor of the Reformation, these marauders sought not only to loot Lima but also to desecrate its sacred churches.

As fear gripped the city, women, children, and members of the religious sought sanctuary within the city’s houses of worship. In the church of Santo Domingo, young Rose took charge, rallying the terrified refugees to prayer. As the pirates breached the church’s threshold, they were met with an awe-inspiring sight. Before them stood a young girl holding aloft a monstrance containing the Blessed Sacrament, her form radiating a brilliant, otherworldly light. Without a word, the terrified pirates turned on their heels and fled back to their ships. As quickly as they had arrived, the pirate fleet set sail, leaving Lima untouched and its people in awe of the miracle they had witnessed. This reported miracle is similar to one that took place in Assisi in 1240, when Saracen soldiers threatened the convent of San Damiano, only to turn and flee when St. Clare held up the Blessed Sacrament.

Forever afterwards, whenever earthquakes struck close by Lima, people believed that Rose’s prayers were the reason Lima was spared.

Whenever Rose spoke about Jesus, her face would radiate with an intense glow, reflecting the profound love she held for Him. Beyond her spiritual fervor, Rose had a special affinity with nature, finding solace and inspiration in its beauty. She was gifted with a melodious voice and composed a beautiful hymn in praise of God, which became her solace during times of suffering. As she struggled through painful illness during the final years of her life, she would sing it many times, pouring out her heart to God in song. It is said that at sunset each day, as she sang from within her room, a small bird would appear at her window. Drawn by the sweetness of Rose’s voice, and perhaps sensing something Divine emanating from it, the bird would join its own sweet song to hers.

Two fellow future saints played crucial roles in Rose’s spiritual journey. St. Turibius de Mongrovejo, the Archbishop of Lima, who confirmed her in 1597, was known for his religious and social reforms, particularly in defending the Indigenous people. Rose prayed fervently for God to sustain him in his trials. The second saint was St. Martin de Porres, a fellow Dominican. He shared Rose’s deep devotion to the Holy Eucharist and dedication to caring for the sick and poor and became her great friend and confidante.

Rose’s devotion to her faith was marked by extreme acts of penance and self-mortification, practices that were not uncommon among devout Catholics of her time, but which she pursued with exceptional intensity. Because she could not be a missionary as she longed to be, she turned to penance instead. “As I cannot do any good,” she said, “is it not just that I should suffer whatever I am capable of suffering?”

She subjected herself to severe physical discomfort, wearing a hairshirt to irritate her skin, an iron chain tightly wound around her waist, and a silver crown of thorns concealed beneath roses. Her dietary habits were remarkably austere for her era; when she wasn’t fasting, she consumed only the bare minimum of food and water necessary to sustain life. When she could no longer stand, she rested on a bed of broken tiles she had made. She later confessed, “The thought of lying down on it made me tremble with dread.” Despite her feelings, she maintained this practice for an astonishing fourteen years. I’ll be addressing Rose’s extreme penances a little later in this episode.

Physically, Rose suffered simultaneously from asthma and arthritis. But her spiritual trials were equally challenging. She endured disturbing dreams and intense temptations against purity and faith, experiences that tortured her mind and left her soul desolate. At times, she felt abandoned by God, believing herself to be revolting in His sight. These periods of anguish were so severe that they visibly altered her appearance, shocking those who observed her tortured expression. Her only earthly support came from her close friend, Brother Martin de Porres, who reassured her that her visions and periods of spiritual dryness were signs of God’s highest favor.

Paradoxically, these trials only drove Rose to intensify her mortifications. Yet, she also experienced profound spiritual consolations. Christ often appeared to her, offering strength and encouragement. She also was comforted by visions of the Virgin Mary and St. Catherine of Siena. One day, Rose found herself deeply troubled, her mind consumed with worries about her eternal salvation. Suddenly, Christ Himself appeared before her, His presence radiating Divine love and compassion. With gentle reassurance, He told her: “My daughter, I condemn only those who will not be saved.” He then bestowed upon Rose three extraordinary promises: First, He assured her of her place in heaven, dispelling her fears of eternal separation. Second, He promised that she would never fall from His grace through mortal sin. Finally, He pledged that Divine assistance would always be available to her in times of need. He also revealed to her the exact day and hour when she would die. This knowledge, far from being a burden, became a source of peace for Rose. It allowed her to approach her remaining days with a sense of purpose and anticipation, knowing that each moment brought her closer to eternal union with her Beloved. During this period of intense spiritual experience, Rose received the grace of mystical marriage with Christ. To commemorate this union, she had a ring engraved with Christ’s words to her: “Rose of My Heart, be My spouse.”

Rose’s extreme practices did not go unnoticed. Concerned individuals suggested that ecclesiastical authorities should investigate her conduct. Summoned before the Archbishop of Lima and a panel of theologians, Rose responded to their questions with brevity and humility. The examiners were impressed by her selflessness and her profound understanding of religious matters, and she was allowed to continue her way of life undisturbed.

Reflecting on the Divine influence that guided her, Rose wrote, “That same force strongly urged me to proclaim the beauty of Divine Grace.”

As Rose approached her twenty-eighth year, she became very sick, causing those around her to fear for her life. However, Rose, with the profound spiritual insight granted to her, knew that her time had not yet come. During this period of illness, her mother seized the opportunity to persuade Rose to part with her hideously uncomfortable bed of broken tiles. Though Rose agreed to have her old bed removed, she remained steadfast in her commitment to self-mortification. Refusing the comfort of a mattress, she instead compromised by accepting plain boards as her new resting place for the duration of her illness.

After recovering from this bout of illness, Rose’s living situation changed. She left the small hut in her family’s garden and, accepting the hospitality of Don Gonzalo de Massa, a Spanish government official, and his wife, she moved into a room in their home. Despite her new living arrangements, Rose’s compassionate spirit remained undiminished. She continued to transform her room into a sanctuary of mercy, welcoming society’s most vulnerable – homeless children, the sick, and the elderly – to provide them with care and comfort.

Rose’s position as a guest in the home of a Spanish official did not temper her outspoken nature. She fearlessly raised her voice against the harsh practices of the Spanish overlords, pointing out their greed as being the root cause of the poor’s suffering. Her courage in speaking truth exemplified her commitment to justice.

On July 31, 1617, Rose fell gravely ill, marking the beginning of her final days on earth. As her condition worsened, she endured intense suffering, including a raging thirst when the doctor forbade her to drink water. Despite her physical agony, Rose’s spiritual radiance seemed only to intensify. Those near her often heard her voice murmuring a poignant prayer: “Lord, increase my sufferings, and with them increase your love in my heart.”

After receiving the holy sacraments, she humbly addressed those gathered around her, seeking forgiveness for any faults and urging them to love God above all else. As death approached, Rose’s joy grew as she anticipated being united with her Divine Bridegroom. Shortly before her passing, she experienced a state of profound religious ecstasy. Upon emerging from this state, she confided to her confessor, “Oh! How much I could tell you of the sweetness of God, and of the blissful heavenly dwelling of the Almighty!” These words offered a tantalizing glimpse of the celestial visions she had seen.

In her final act of earthly penance, Rose asked her brother to remove the pillow from beneath her head, so she could die on bare boards, just as Christ had died on the cross. With the pillow removed, Rose bid farewell to her loved ones and asked God to comfort her mother. In her final moments, she uttered the words: “Jesus, Jesus, be with me!” Rose passed away just after midnight on August 24, 1617, the feast day of St. Bartholomew the Apostle.

Remarkably, Rose’s mother did not succumb to grief upon her daughter’s passing. Instead, she was overcome with an inexplicable joy, so profound that she hurried to another room to conceal her emotions. This joy spread throughout the household and the town, with a collective decision made to forgo mourning in favor of celebration. The profound impact of Rose’s life and death, and the esteem in which she was held, was evident in the extraordinary nature of her funeral procession. The Canons of the Church led the way, carrying her body for part of the journey. They were followed by the Senate, evidence of how Rose’s influence had reached even the highest echelons [ESH-ah-lons] of civil authority. Finally, the Superiors of various religious orders took their turn, each group eager to pay homage to a woman whose holiness had touched and inspired so many. This remarkable funeral procession, with its diverse participants, was a fitting tribute to a life that had bridged the gap between the earthly and the Divine, between the humble and the exalted.

The impact of Rose’s life and death was immediate and profound. Abundant miracles began to occur following her death. There were reports that she had cured a leper, and that the city of Lima smelled like roses; some claimed they witnessed roses falling from the sky. The people of Lima clamored for her immediate canonization; however, due to a recent Papal ruling requiring a 50-year waiting period between death and canonization, Rose’s official recognition as a saint was delayed. She was beatified by Pope Clement IX in 1667 and canonized by Pope Clement X in 1671, becoming the first person born in the Americas to receive this honor.

One of the most popular saints in the history of the Church, Rose of Lima is the patron saint of Latin America and the Philippines, of embroiderers, gardeners, florists, people who are ridiculed for their faith, and those who suffer with family problems. Her feast day has undergone several changes in the liturgical calendar. When first inserted into the General Roman Calendar in 1729, it was celebrated on August 30. This date was chosen because August 24, the anniversary of her death, was already occupied by the feast of Saint Bartholomew. In 1969, Pope Paul VI revised the liturgical calendar, making August 23 available for Saint Rose’s feast day. This change was implemented worldwide, including in Spain. However, Peru and some other Latin American countries continue to celebrate her feast on August 30, which remains a public holiday in her honor.

In art, St. Rose is often portrayed wearing a crown of roses and holding a cross, or a heart with a cross. Her symbols also include roses and lilies, and she is often portrayed with a brown habit, as a reference to her religious vocation as a Third Order Dominican.

WAS ST. ROSE TOO EXTREME?

Since I always strive for honesty with my readers, I must confess that I sometimes struggle to relate to saints like Rose of Lima who engaged in extreme, even bizarre, practices of penance and mortification. While I deeply admire these saints, their behavior can seem peculiar, even potentially unstable, when viewed with the perspective of modern times. Moreover, it’s challenging to see them as relatable role models, because their practices appear far beyond what most ordinary 21st-century Christians could or would aspire to.

In researching St. Rose of Lima for this episode, I was genuinely shocked by some of the facts I uncovered. In a book called Voices of the Saints, author Bert Ghezzi writes of St. Rose: “She fasted often. Sometimes she made herself vomit after meals, which today would probably be regarded as bulimia. She prayed long hours and frequently beat herself with a little whip.” Other sources mention that a spike in the silver crown she wore became so deeply embedded in her skull that its removal was extremely difficult. Then there’s the matter of her “bed” – used for only two hours of sleep a night – filled with broken tiles, pottery shards, and thorns. She also suffered from scrupulosity, today considered a form of obsessive-compulsive disorder, which involves excessive guilt and anxiety about sin and moral or religious issues.

This all seemed so extreme that I nearly decided against producing this episode. However, in my quest to better understand the saints, I delved into the subject of asceticism, which is the practice of self-discipline and self-denial, and the issue of extreme mortifications. I’d like to share my findings and conclusions with you.

Lest we think that asceticism is something peculiar to Catholic Saints, it’s important for us to realize that it has its roots in ancient human attempts to achieve various goals and ideals. Originally, it was closely tied to athletic training, where Greek athletes would abstain from gratification and endure physical challenges to prepare for competitions like the Olympic Games. Warriors also adopted similar practices to excel in combat, with ancient Israelites even abstaining from carnal relations before battle.

Over time, the concept of asceticism expanded beyond physical training to encompass mental, moral, and spiritual development. Across many religions and times, people have used asceticism to grow spiritually and connect with the Divine. In older tribal religions, asceticism was important too. Coming-of-age rituals play a significant role in many cultures, particularly among Native American tribes. These ceremonies mark the transition from childhood to adulthood and often involve challenging physical and spiritual experiences, such as the Vision Quest. This consists of isolation in nature for 2-4 days, often at sacred sites; fasting and prayer to seek spiritual guidance; hoping for a vision or dream that provides life direction; and guidance from elders in interpreting the experience. This closely resembles the visions and revelations of many of the saints who practiced extreme fasting, prayer, and isolation.

In major religions like Hinduism, Buddhism, and Christianity, people turned to asceticism because they realized life on Earth is fleeting, so they wanted to focus on the afterlife. They pushed back against worldly things, believing a simple life was more spiritual. In Christianity, asceticism took many forms. In the Gospels, Jesus did not directly talk about asceticism, but His followers were inspired by His simple life. St. Paul, in his letter to the Corinthians, compared Christian life to an athlete in training. Early Christians often fasted, stayed up all night praying, and avoided physical gratification. Some Christians took these practices to extreme levels. The Desert Fathers (early Christian monks) taught that self-denial or “mortification” is a tool, not the main goal. They advised being careful with these practices and said that harsh forms should be done only with guidance from an experienced spiritual teacher. They believed it is wrong to practice self-denial for physical gratification or because of scrupulosity.

As I examined the life stories of saints who engaged in extreme penances, I noticed a pattern. Many, though certainly not all, were initially young, healthy, and born into households of wealth and luxury. Given that adversity and some degree of suffering are necessary for spiritual growth – a belief shared by many religions – it appears that these individuals, lacking natural hardship, felt compelled to reject their comfortable lifestyles and create ways in which to suffer. But the idea of manufactured suffering can seem perplexing and unnecessary for those of us born into less fortunate circumstances, who have experienced struggle and adversity in daily life, have serious disabilities, or who are experiencing the aches, pains, and health problems that come with simply growing older.

Many saints besides Rose of Lima engaged in severe forms of self-mortification as a means of spiritual growth and penance, including Gemma Galgani, Catherine of Siena, Ignatius of Loyola, Dominic, Francis of Assisi, and Thomas More, to name just a few. Today, such extreme practices might be viewed as symptoms of mental health issues like obsessive-compulsive tendencies, eating disorders, and self-harm behaviors. But it’s important to view them in the context of their own times, realizing that these practices often were accepted and even encouraged in certain historical and cultural settings.

Saints typically undertook these penances out of deep devotion and a desire for spiritual growth, not due to mental illness or reasons of vanity or physical gratification. For instance, anorexia and bulimia normally arise from a distorted body image and excessive fear of weight gain, whereas spiritual fasting is practiced in many religions as a way to deepen one’s connection with God, cultivate humility, resist temptation, and seek God’s guidance. St. Rose of Lima’s actions to spoil her beauty were primarily motivated by her determination to avoid marriage and fulfill her vow of virginity, rather than for self-harm purposes. Since young women of her time had very little say in choosing their own path in life, they sometimes had to resort to desperate measures.

The saints believed that anything that might jeopardize their relationship with God had to be eradicated. Prayer, fasting, self-denial and mortifications were their way of achieving this goal. Most of the saints practiced mortification under the guidance of spiritual directors, showing a level of restraint and obedience. Many saints were discouraged from severe mortifications by their spiritual directors, St. Francis of Assisi being one notable example of this. St. Rose’s obedience to spiritual authority, too, was absolute. When her confessor forbade a particular penance, she would immediately cease the practice until given permission to resume or substitute another form of mortification. (We can only imagine the practices she was forbidden to do)! By the time of her death, she had nine spiritual directors, and all of them testified that her penances had been Divinely inspired, because of her humility and obedience.

While we can appreciate the devotion of these saints, in modern times it’s important to approach such practices with caution and discernment. Canonization does not imply that every action of a saint should be imitated; it simply affirms that the person is in heaven. Stories of extreme mortification often capture our attention and stick in our memory, which may lead to their overemphasis in religious instruction.

The Church has shifted focus towards emphasizing the fundamental goodness of the body and creation, and discourages extreme forms of bodily mortification that could be harmful or counterproductive. Mortification should be purpose-driven, a means to spiritual growth, not an end in itself. It should be part of a balanced spirituality in which the focus is on overall virtue and holiness, not just physical austerity.

Many Catholics practice “everyday internal mortification” by offering up daily discomforts or challenges as a form of spiritual discipline. I always like to start my day with a prayer called “The Morning Offering,” which offers to Jesus all the prayers, works, joys and sufferings of the day. Although this seems pretty lame in comparison to St. Rose’s heroic penances, on days when my joints hurt or I’m facing a particularly stressful situation, I like to think that my offering it up to God will at least make it a little more meaningful.

Modern Catholic devotional practices that aim to foster a deeper spiritual connection and devotion to God without resorting to extreme physical acts include: Novenas dedicated to specific saints or intentions; Eucharistic adoration; praying the Rosary; making the Stations of the Cross; wearing scapulars or religious medals; and pilgrimages to holy sites or shrines; fasting and abstinence during Lent and other prescribed times; voluntary acts of self-denial, such as giving up certain comforts or gratifications; offering a sickness or discomfort for our own sins and those of others; and practicing patience and charity in difficult situations. This last one is especially challenging for me, so much so that I have created an episode about it called “How to Become More Patient.” If patience is difficult for you as well, you might be interested in checking it out. I have included the link here: HOW TO BECOME MORE PATIENT: 7 TIPS | Everyday Life Spirituality

In this day and age, when most of us live in relative comfort, we are subject to temptations to overindulge in many things: Food, drink, entertainment, physical relationships, attachment to electronic devices, etc. We are bombarded every day by ads urging us to acquire more and more “stuff,” most of it trivial, useless, and excessive. Although we might shudder in horror at the voluntary disciplines undertaken by St. Rose of Lima, maybe it can at least inspire us to practice a little self-restraint and self-denial as we are able, for the benefit of our own souls.

Rather than merely dismissing her as too extreme, we can remember St. Rose of Lima’s admirable spiritual virtues and the way she lived out her life in true imitation of Jesus Christ, rather than just her severe penances. Although her earthly journey was brief, the impact of her immense faith, compassion, charity, and courage in the face of opposition, ridicule and severe temptations, has endured over the centuries. Let’s ask her today to make us stronger Christians, too.